The flamboyantly punctuated Tyler Brûlé, the known global style guru and editor in chief of Monocle magazine, has in recent weeks shown strong interest in nation branding and country brands. In ‘Fast Lane’, his weekly column at the Financial Post, the chieftain of “the Lufthansa audience”, as he calls Monocle’s reader base, has touched the isse on several occasions in the last months.

In his November 13th column, titled ‘Brand Korea: soft power, hard sell’, Mr. Brûlé focused on South Korea’s brand image and stated that

In his December 3rd column, Brûlé turned his attention to ‘Brand Italy’, writing the following:

In the current issue of Monocle we did a ranking of the world’s top “soft power” players (the UK and France came first, followed by the US) and it was both surprising and sad to see Italy rank a distant 16. Given all of the Italian brands and cultural exports that touch people’s lives it’s surprising that it didn’t put in a better showing in the ranking. But when you consider the damage that Silvio Berlusconi, its prime minister, inflicts daily on Brand Italia it’s remarkable it manages to even make the top 25.

For the better part of six years this column has occasionally argued that Italy would be a frightening global force if it could field and elect dynamic and competent leaders, fix its airline, produce better television and encourage its manufacturing power base to stop resting on the laurels of an increasingly dubious Made in Italy label. Fortunately, Italia has a lot of natural resources (sea and mountains; food and drink; a knack for doing the most remarkable accessorising with any type of scarf) and indigenous structures (strong family enterprises; grumpy but dependable waiters in white jackets; an ability to make remarkable pieces of furniture out of virtually any material) working in its favour and keeping it solvent (for the moment).

In his Christmas Eve piece, Brûlé looked at the United Kingdom, highlighting how the pathetic performance of Britain’s airports in the last weeks had impacted on Brand UK. “Rather than asking why a developed economy such as the UK should be buckling under a cold weather snap and a blanket of snow (just a dusting in some areas), most of the media just ran with stories of stranded travellers, road chaos and a system that wasn’t coping. What was missing from most of the coverage was the all-important, ‘Why isn’t the UK able to deal with this and what does it do for the nation’s brand?'”, he asked.

He continued and elaborated,

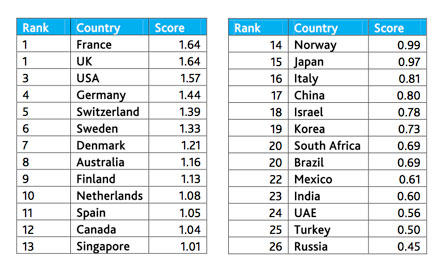

But Tyler Brûlé does not refer to nation branding from his personal column at the Financial Times only. His magazine is also circulating around the concepts of nation branding and soft power in the December issue. The latest edition of Monocle has a ranking of countries by “soft power”— ‘the ability of a country to get what it wants in the world by using its own sense of legitimacy and attractiveness’, as the editors define it.

The survey was made in collaboration with the Institute for Government, and these are the results from the index:

Countries are commented one by one across the magazine’s pages. For instance, Canada, which is Brûlé’s native country, is considered “strong on soft diplomacy but is not a superpower”. According to the Monocle editors,

Part of Ottawa’s problem is that much of what it does on the world stage is refracted through a US prism. Female chanteuses and Cirque de Soleil aside, Canada doesn’t make quite as big a cultural contribution as it could. The CBC could easily be an alternative international voice to the BBC but it’s not. Canada could also boast a strong international newsweekly to push a slightly different Americas agenda but it’s seemingly content to play within its own borders.”

And herein lies the problem, Canada is very content with its lot. While it threw considerable resources at Afghanistan and was a key player in Haiti, it could have gone much further with the latter. Looking north, the issue of Arctic sovereignty is looking for a leader and Canada should be manning this bridge as everyone scrambles for shipping routes and resources.

Tyler Brûlé’s consistent interest in nation branding and country brands is noteworthy because Mr. Brûlé is a trend-setting icon. He exerts great influence on that unlucky part of the world population who spend their busy lifes in airports, in aircrafts and in executive boards. In short, the kind of people who drive the world, for good or for worse. So Mr. Brûlé can make, and in fact is making, the whole subject of nation branding more widely known and raise it from the secrecy of ministries of Foreign Affairs, the rigid boringness of FDI agencies and the obscurity of tourism boards.

Luckily enough, it’s also encouraging to notice that Brûlé is not broadcasting a kind of unsubstantiated, superficial ‘nation branding’ as some would prejudice. Instead, he understands that nation branding is not about logos and slogans, but about nation brands, national identity, national strategies in global affairs, soft power, national performance and national reputation management.

Whether Tyler Brûlé’s influence will allow nation branding to become a more popular concept among the elites who rule the world is yet unknown, but what’s certain is that one can hardly imagine a better platform for nation branding than that of the Financial Times and the Monocle magazine combined.

Article by Andreas Markessinis

….but what’s certain is that one can hardly imagine a better platform for nation branding than that of the Financial Times and the Monocle magazine combined.

True.

I personally observe the Anholt NBI for more than 4 years now. Tyler Brulé and his Monocle is also closely followed since the inception of the magazine.

I found it logic even inevitable that Brulé finally gets more intruiged by the NBI concept.

For me as the main author and main designer of Wikipedia Germany & Berlin (see the link), I was always aware that Brulé and his editorial staff gathers information from Wikipedia and subsequently reads or better watches the articles.

So I was pleased when Monocle presented Germany at 4th place in its Brand Ranking, while at the same time citing some crucial

parts from the Germany article.

I do believe that the concept of nation brands (not branding) and national reputation is not yet fully spread enough.

Nevertheless I believe the Anholt NBI is revolutionary, I even dare to predict that Anholt one day will get a Nobel Prize in Economics for this…..